How Roger Waters Reanimated His Legend on ‘Amused to Death’

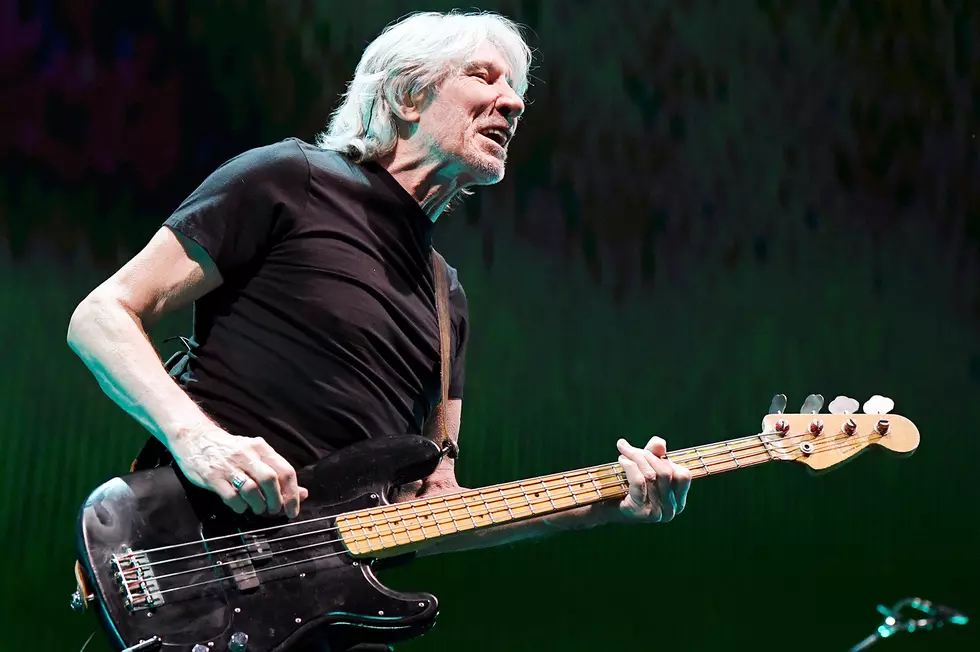

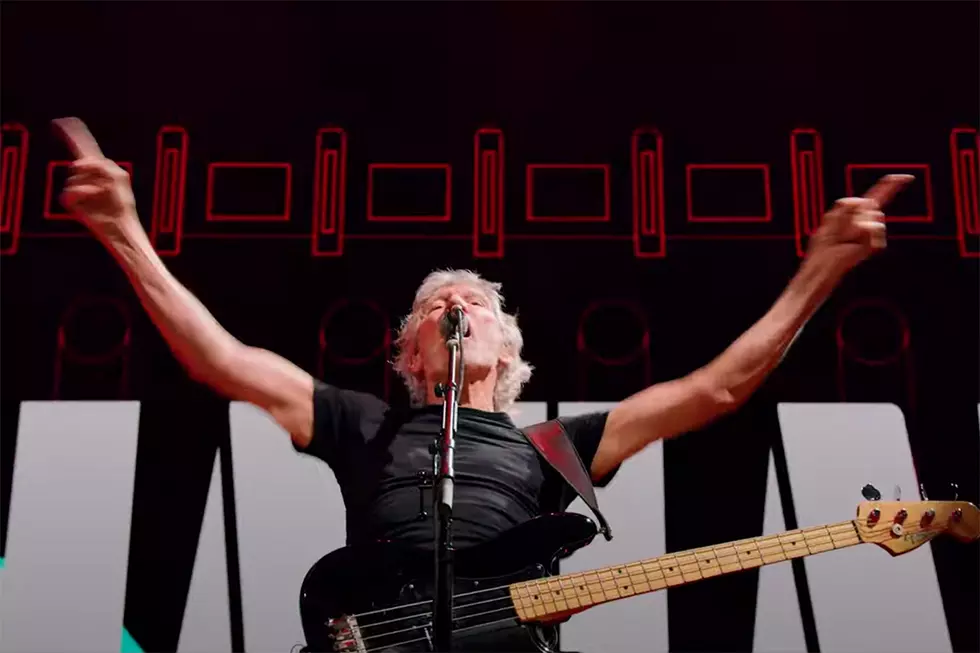

Even though he served as the primary creative force in Pink Floyd for a decade starting in the early '70s, Roger Waters' foray into solo work suffered from inconsistency, repetitiveness and creative drought. That changed when he found a fresh angle on a tried-and-true formula with Amused to Death, released on Sept. 1, 1992.

Waters again focused on the problems of modern life, including rampant greed, bureaucracy, egotism and war. In the broadest sense, he'd been talking about these issues for decades. What was lacking more recently, in particular on 1987's confusing, too-wordy and too-synthy Radio K.A.O.S., was both a sense of narrative cohesion and Floyd's familiar musical dimension.

Amused to Death deftly solved both issues, emerging as the best Pink Floyd-related release during a period dominated – at least commercially – by the transitional and ultimately unsatisfying A Momentary Lapse of Reason.

First, Waters stripped everything back in the studio, recording with a core group of smart sessions players that included Jeff Porcaro, Randy Jackson and Patrick Leonard. "I was certain when I started making Amused to Death that I would make it in absolutely bone-simple traditional methods with real people playing real instruments," Waters told the Los Angeles Times in 1992.

If the results sounded just like Pink Floyd, there was a reason for that too. Amused to Death was completed with help from longtime orchestral collaborator Michael Kamen, who'd earlier worked on the band's The Wall and The Final Cut. Importantly, Waters also forged a collaborative bond with a forceful and equally artful guitarist. Only this time, instead of David Gilmour, it was Jeff Beck. The former Yardbirds legend appeared on seven cuts, providing thrillingly angular asides.

Next, Waters explored a lyrical twist, viewing everything through the prism of our mindless obsession with media. Impressed with the anti-television tack taken in a book by Neil Postman called Amusing Ourselves to Death, Waters chose a similar name. As session work continued, Waters then updated the material to include references to the massacre at Tiananmen Square and Operation Desert Storm – both of which had drawn huge cable-watching audiences.

Listen to Roger Waters' 'Watching TV'

"I've always been intrigued by this notion of war as an entertainment to mollify the folks back home – and the Gulf War fueled that idea," he told Rock Compact Disc Magazine in 1992. "Amused to Death deals with the idea of whether TV is good or bad. And I set out to show that it can be both."

That's how the album-opening "Ballad of Bill Hubbard" came to include a sample from a broadcast documentary where veteran Alfred Razzell discussed his experience in World War I. "There was always a question mark in the back of my mind as to how relevant it was to include his dialogue," Waters added in the talk with Rock Compact Disc. "I found it very moving, but I didn't know whether anybody else would. So far, the reaction from those people who have heard the record has been favorable; they're making the connection. That original program confronted the horrors of war and told the real story. It was an example of television taking its responsibilities seriously."

Later, "What God Wants, Pt. 1" revealed perhaps Waters' best take on the conflicts within organized religion. Equally trenchant was his contempt for warlords in "The Bravery of Being Out of Range," excoriating the modern-day trend of remote-control warfare. At the same time, however, there was more to Amused to Death, something that appealed to the heart as well as the head. For instance, a finely detailed duet with Eagles co-founder Don Henley called "Watching TV" used his fictional account of a doomed protester in the 1989 Chinese youth movement against Communism as a vehicle to create the most sadly beautiful thing Waters has ever done.

"In the more than five years it took to make this record, my songwriting has become more passive, more of a conduit, with less ego," he told Billboard in 1992. "And it now allows me to attach more directly to the individual experiences I'm writing about. Like that of the imaginary girl in Tiananmen Square. It allows me to enter her mind, to give her an engineer for a father and a part-time job as a pastry chef, and it allows me to weep for her. Maybe I've succeeded in the last five to 10 years in tearing down more of my own wall."

Watch Roger Waters' 'Three Wishes' Video

"Three Wishes" found Waters admitting that a constant focus on the big picture can sometimes have very real consequences at home. "It's the old three wishes story," Waters told Rockline in 1992. "You know, the genie comes out of the bottle and before you know it, you've had your three wishes and you never got 'round to the thing you really wanted. In this case, true love." His title track drove home the album's overarching theme, but was preceded by the surprisingly hopeful "It's a Miracle."

"There is stuff there for people to take for their own, if they're prepared to," Waters told Top Magazine in 1992. "I hope people can understand it and that some of them may realize that they're not alone. Maybe we can gather together in small groups and make the world a better place."

He emerged with well-founded high hopes – "I think it's a stunning piece of work," Waters said in Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd – yet still had to resign himself to the fact that Amused to Death would have reached a much wider audience had it been released under his old group's name.

"I expected more people than did to know who I was and what I'd done – but they didn't, and they still don't," Waters told the Los Angeles Times. "If Amused to Death is a success, a large percentage of the people who buy it will not make the connection between me and that band. And that's okay. In some ways, I'd rather they didn't."

Nevertheless, Amused to Death rose to a very respectable platinum status, and finished at No. 8 in the U.K., becoming his highest-charting album. Waters was, quite simply, finally back on his game. An out-of-the-box narrative approach was emboldened by widescreen and prototypical Floyd-sounding music that finally matched Waters' trademark lyrical intensity once again.

Top 50 Progressive Rock Albums

Why Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour and Roger Waters Are Still Fighting

More From KLTD-FM